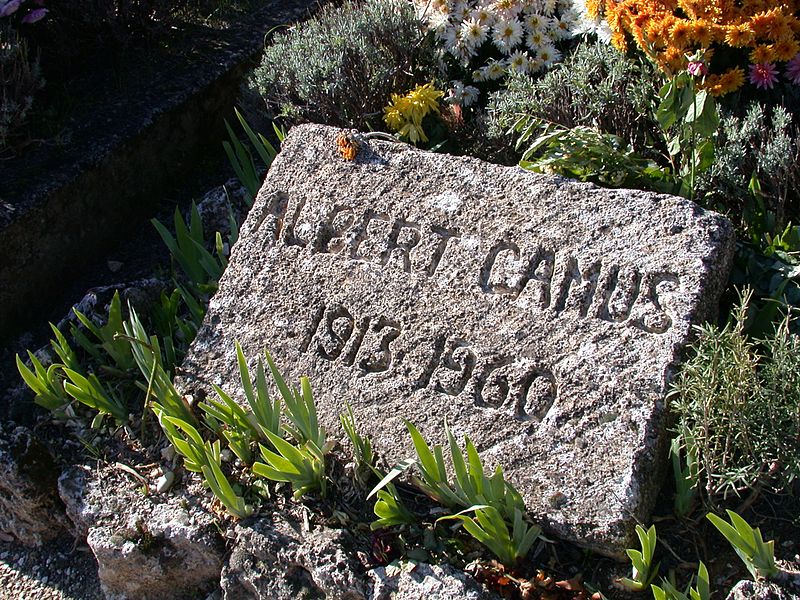

A few years ago, on a holiday in Provence, I dragged my family to the village of Lourmarin to visit the grave of Albert Camus. Lourmarin is a pretty, well-preserved medieval town, but the nondescript cemetery outside its walls must be its least alluring feature. The graveyard was hot, dusty, and indifferently tended. My wife recalls the place as "depressing." But for me it was, in Michelin-guide terms, worth the journey to pay my respects to Camus.

There are not many authors I would classify as my heroes, but Camus is one of them. He was not just a superb writer, but a courageous man. Camus edited a Resistance newspaper during the occupation of France, and throughout his life consistently stood up for individual choice and dignity in the face of all forms of oppression and conformity--whether Stalinism, Naziism, or religious orthodoxy.

Camus' gravestone is simple and unadorned: just his name and dates. It took some time to find, because it was not specially marked. I stood by the slab for a few minutes. In the hot August afternoon, the Provençal sun pressing down on my head, I thought of the shimmering heat of the beach in Algiers, indelibly rendered in The Stranger. The humility of this resting-place touched me; it seemed perfectly suited to the man who lay there.

Now France's president, Nicolas Sarkozy, is lobbying to move Camus' remains to the Panthéon, the imposing (some would say bombastic) tomb that holds other great men and women of France--Voltaire, Victor Hugo, Marie Curie. His plan has stirred a heated controversy. It seems like the rankest ploy of an unpopular politician hoping to appropriate the aura of a figure revered in France. But even if Sarkozy is acting from the best of intentions, to move Camus from his provincial grave to the Panthéon is a stunningly wrongheaded idea. While Camus' daughter has apparently assented to the scheme, his son Jean is sticking up for the Lourmarin cemetery. The move, he says "would be contrary to his father’s wishes and [he] does not want to have his legacy put to work in the service of the state."

Jean is right. Camus should be allowed to remain in his quiet, sun-baked plot in the south of France--closer to his native Algeria and far from the machinations of the Elysée Palace. The Pantheon speaks of the greatness of France, but not the humanity of Camus.