I recently learned of writer Douglas Morrison's blog,

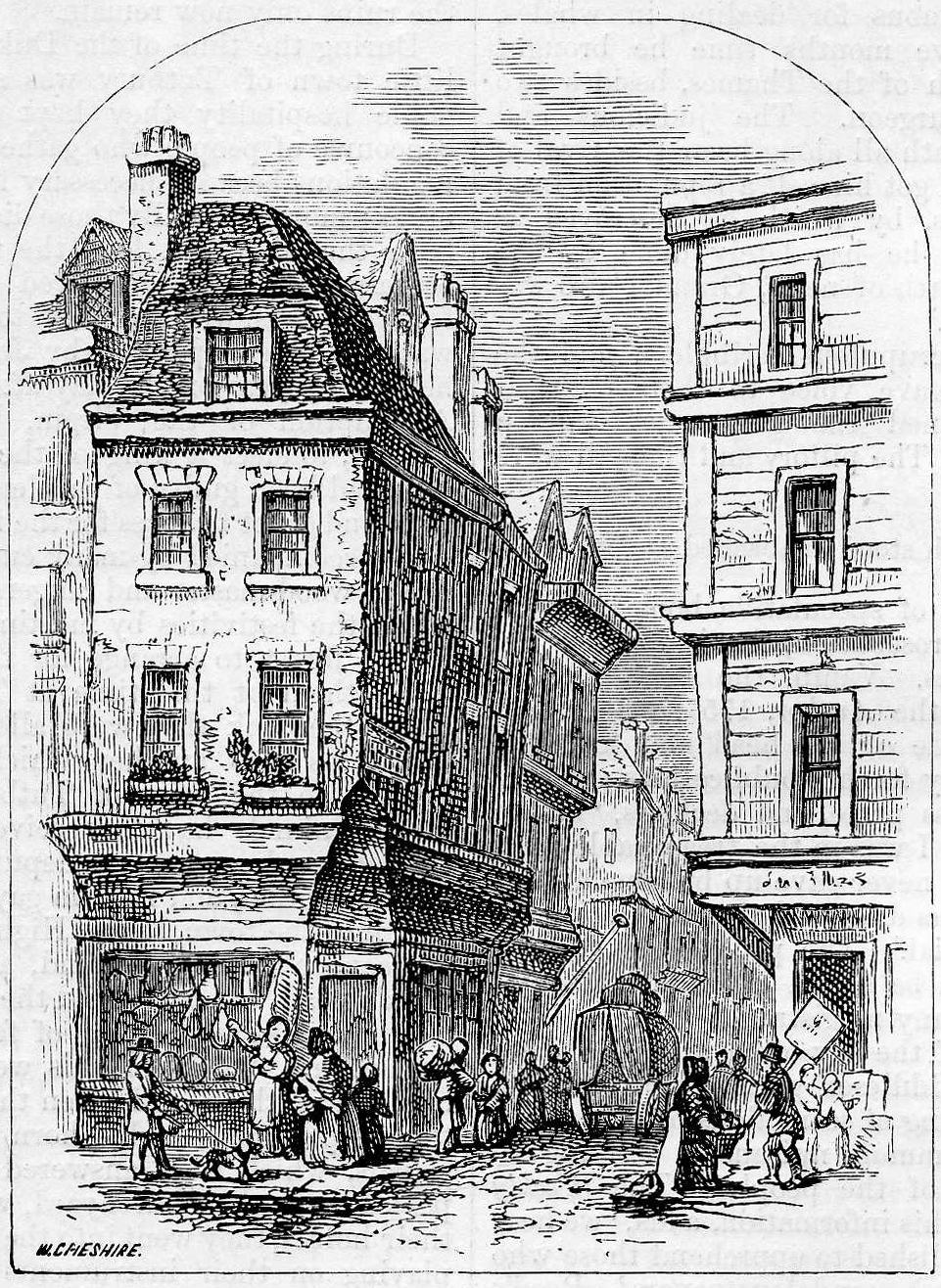

The Novel Road, which is worth a visit for anyone interested in the writing trade, especially the fiction side of it. He posts links to a variety of other blogs and articles, and has been conducting his own series of author interviews, with writers such as Brian Haig, Robin Becker, and Dale Brown. Doug flattered me by including me among his interviewees this month, asking a lot of good questions about editing and publishing, which I answered to the best of my ability. The best part is that Doug included two of Thomas Rowlandson's satirical images with his post. (The one here is captioned

Dr Syntax, in the middle of a smoking hot political squabble, wishes to whet his whistle.The Doctor is in black by the fireplace, next to one of the smoking squabblers.)

Here's the Q & A, with thanks to Douglas Morrison:

Doug Morrison: Do you have a character, from a manuscript you have edited, that has left a mark on you?

PG: Many, so I’ll

pick one from a manuscript I’ve just published: Stephen Douglas, who

lost the presidential election of 1860 to a dark-horse candidate named

Abraham Lincoln. Douglas was on what we’d consider the “wrong” side of

the slavery issue, and he had often acted from expediency and ambition.

But when he knew he was about to lose the office he had coveted for his

whole career, Douglas barnstormed the country trying to hold the Union

together. He literally died trying to prevent the Civil War. The story

is told Douglas Egerton’s book Year of Meteors, and I found it surprisingly moving.

DM:

DM:

The editor in you must have an intuition for the “special” book; the

one that seems destined to huge sales or a place in literary history.

Among the books you have worked with, what made your “I knew it” list?

PG: The

humbling thing about being an editor is the flip side of your question:

how many of the books you know are special never achieve the sales they

deserve. That’s much more common than thinking “I know it” and seeing

the title on the bestseller list. But it’s exciting when you’re right. I

knew David Hackett Fischer’s Washington's Crossing was a masterpiece

when I first read it—it was brilliantly researched, wonderfully written,

and thrilling to read. It became a New York Times bestseller and won

the Pulitzer Prize for history. But I have had the same feeling about

other books that never hit the jackpot that way.

DM: The editors

I’ve researched, seem to stick to comfort zones when they choose a

manuscript. Have you ever gone outside your comfort zone?

PG: I’d hate to think I always publish in a

“comfort zone,” because I think you should always be looking for works

that challenge you and that are different from what you have done

before. At the same time, it’s hard to be a good publisher for a MS you

don’t know anything about or you’re not enthusiastic about. For

instance, my politics are moderately liberal, but I’m always ready to

publish books that make good arguments for conservative positions, or

far-left ones for that matter. On the other hand, I’d never be the right

editor for a book on organic gardening, because I’m not a gardener of

any kind. I don’t think you should edit a book that you’d never buy in a

bookstore. To publish something well, you have to know how to connect

with its intended reader. So I don’t ask, “is this in my comfort zone?” I

ask, “do I know who would want to read this and how I’d get them

excited about it?”

DM: Publishing Non-Fiction has a higher degree of

speculation (i.e. advances, deadlines) than Fiction Publishing. Is this a

true statement?

PG: To use a favorite publishing phrase: it depends.

In general the advantage of publishing nonfiction is that you can

identify the audience for it and have some idea how to reach that

market—whether it’s organic gardeners, Obama-haters, Civil War buffs or

dog lovers. You can make some guesses about the market based on how

other titles have performed. In fiction, it’s much more unpredictable,

with the major exception of genre fiction. Historical romances, cozy

mysteries, steampunk, anything in a series –those niches help you target

the readership. But for many novelists it’s hard to predict how a new

work will sell, so it’s highly speculative. In general I’d say fiction

is more of a guessing game for a publisher.

DM: What is Bloomsbury Press looking for right now?

PG: That’s a question I’m always reluctant to

answer, because there aren’t one or two things we’re “looking for.” We

are always looking for well-written books that have something

interesting and preferably original to say, on a subject of importance. I

have written more about this on our website,

bloomsburypress.com.

DM: I send you a 150,000-word manuscript. It’s a mess,

the title is even misspelled , but you read the first page and it

catches your interest. Do you send it back with a note explaining,

“Spell Check”, margins and sentence fragments, or do you keep it? What

state do you like to see a manuscript in before you work on it?

PG:

In all honesty, if you can’t spell the title I’m not going to read much

further unless your first paragraph is stunningly brilliant. Authors

who can’t achieve a baseline level of professionalism are, in my

experience, extremely unlikely to write a book that can be published

with success.

DM: How much author editing is too much? Where should an author stop editing before submission?

PG: Keep editing until it’s really good, but by that

I don’t mean “tinker obsessively with your MS for months.” Get

feedback—candid feedback—from readers you trust. I work with a lot of

scholars. In the academic world, even the most senior authors routinely

show their drafts—sometimes single chapters, sometimes whole

manuscripts--to other people who know their subject really well, and get

their comments. It amazes me how often an author will say something

like “I showed this to three readers and they all thought it was the

best thing I’ve done,” and it turns out the readers are her husband, her

mom and her next-door neighbor. Find some readers who aren’t afraid to

tell you your script is boring, and get their comments.

DM: Freelance editors, hired by authors. The consensus

with literary agents seems to be an author doesn’t need one. You would

think a closer to finished manuscript would cost them less to move

forward?

PG: I don’t know which agents you have talked to,

but I question that “consensus.” Most of the agents I know tell me it’s

getting harder to sell anything that needs work, because editors are

reluctant to take on really time-consuming projects. And I know a lot of

freelance editors who are being hired by authors and agents to get

their work ready to submit to publishers.

DM: I’ve written about how I think editors may be going

into a “Gold Rush” market for their skills. I base this on the

increasing number of fairly sloppy e-books that seem to make it onto the

market. Will Amazon, Barnes and Noble, etc, have to address this

problem? If so, what’s your solution?

PG: I’m not sure what problem you’re referring to.

The sloppiness of e-books is often a problem not in the writing or

editing, but in the conversion of print book text to e-book format. This

is a matter, more or less, of proofreading, not “editing” of the kind

that I do. And I think it will dwindle away as publishers learn to plan

their work flow to incorporate e-books. That said, I am sure that the

skill of editing manuscripts and preparing them for publication is one

that will continue to be needed, in whatever format books are produced.

DM: I’ve written a post on literary agents, in an

ongoing series I call “Writer’s Angst”. What would you like writers to

know about the world of the editor? The Publisher?

PG: Even though we have to say no to 95 percent (or

more) of the submissions we receive, no editor was drawn into this

business by the idea of turning people down. We’re always hoping that

the next thing we read is going to be something that we love.

DM: Dr. Syntax

is an incredible site, offering insights to both new and experienced

writers. How do you find the time to blog and maintain the incredibly

high standards at Bloomsbury Press, as well as have a personal life?

PG: Thanks for all those flattering adjectives. I

squeeze the blog in as best I can, and readers will probably notice that

I sometimes go a long time between posts, which mostly reflects how

much else is going on in my working life at any given time.

DM: You wake up one day and decide to pitch it all to write a great book. What would the subject be and who would edit it?

PG: I have often thought I’d like to write about the

history of publishing in the early 20th century, which is so often held

up as a golden age. I’d love to examine how the dynamics of the

industry worked. I suspect the book business in Maxwell Perkins’ day was

closer to ours than we commonly believe.

DM: The Publishing Industry is facing enormous

challenges in the not so distant future. A number of smaller Houses have

closed, Literary Agencies are taking on fewer, if not more select

clients. Paint us a picture of the Publishing Industry five years from

now.

PG: Predicting the future of publishing even two

years from now is probably impossible. But I think within ten years it

will look very different. E-books will be a much bigger piece of the

market, but we don’t know whether they’ll be the predominant format.

Conversely, retail bookstores will be many fewer in number. The

shrinking of retail space is going to hurt the revenues of publishers,

big publishers in particular, and we may well see more consolidation of

major houses. I suspect author advances will go down on average—again I

mean at the larger houses. Meanwhile I think we’ll see an increase,

maybe an explosion, of alternatives to the big-house model of

publishing. Smaller houses, e-book-only publishers, houses that sell

books on a subscription basis as well as conventional print sales. Maybe

every bookstore will have an Espresso machine printing books on demand

in the front window.